Recently I set out to hold a

Battleship programming

tournament here among some of the undergraduates. Naturally, I myself

wanted to win. So, I got to thinking about the game, and developed what

I like to call "the linear theory of battleship". A demonstration of the

fruits of my efforts can be found

here. Below, my

aim is to guide you through how I developed this theory, as an exercise

in using physics to solve an interesting unknown problem. This is one of

the things I really love about physics, the fact that obtaining an

education in physics is essentially an education in reasoning and

thinking through complicated problems, along with an honestly short list

of tips and tricks that have proven successful for tackling a wide range

of problems. So, how do we develop the linear theory of battleship?

First we need to quantify what we know, and what we want to know.

The Goal

So, how does one win Battleship? Since the game is about sinking your

opponents ships before they can sink yours, it would seem that a good

strategy would be to try to maximize your probability of getting a hit

every turn. Or, if we knew the probabilities of there being a hit on

every square, we could guess each square with that probability, to keep

things a little random. So, let's try to represent what we are after. We

are after a whole set of numbers $$ P_{i,\alpha} $$ where i ranges

from 0 to 99 and denotes a particular square on the board, and alpha can

take the values C,B,S,D,P for carrier, battleship, submarine, destroyer,

and patrol boat respectively. This matrix should tell us the probability

of there being the given ship on the given square. E.g. $$ P_{53,B} $$

would be the probability of there being a battleship on the 53rd square.

If we had such a matrix, we could figure out the probability of there

being at hit on every square by summing over all of the ships we have

left, i.e. $$ P_i = \sum_{\text{ships left}} P_{i, \alpha } $$

The Background

Alright, we seem to have a goal in mind, now we need to quantify what we

have to work with. Minimally, we should try to measure the probabilities

for the ships to be on each square given a random board configuration.

Let's codify that information in another matrix $$ B_{i,\alpha} $$

where B stands for 'background', i runs from 0 to 99, and alpha is

either C,B,S,D, or P again, and stands for a ship. This matrix should

tell us the probability of a particular ship being on a particular spot

on the board assuming our opponent generated a completely random board.

This is something we can measure. In fact, I wrote a little code to

generate random Battleship boards, and counted where each of the ships

appeared. I did this billions of times to get good statistics, and what

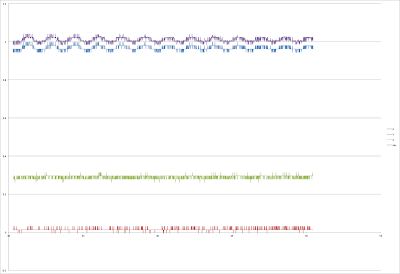

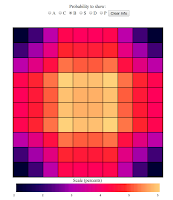

I ended up with is a little interesting. You can see the results for

yourself over at my results exploration

page by changing

the radio buttons for the ship you are interested in, but I have some

screen caps below. Click on any of them to embiggen.

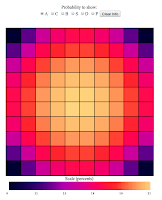

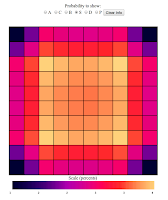

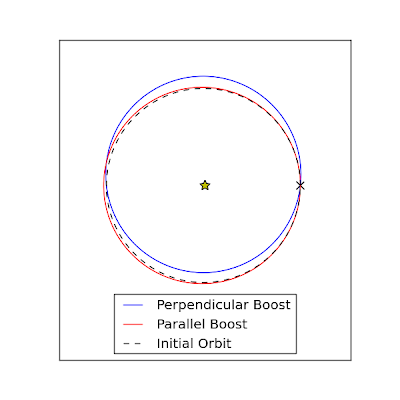

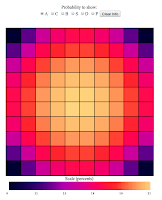

All

First of all, lets look at the sum of all of the ship probabilities, so

that we have the probability of getting a hit on any square for any ship

given a random board configuration, or in our new parlance $$ B_i =

\sum_{\alpha={C,B,S,D,P} } B_{i,\alpha} $$ The results:

shouldn't be too surprising. Notice first that we can see that my

statistics are fairly good, because our probabilities look more or less

smooth, as they ought to be, and show nice left/right up/down symmetry,

which it ought to have. But as you'll notice, on the whole there is

greater probability to get a hit near the center of the board than near

the edges, an especially low probability of getting a hit in the

corners. Why is that? Well, there are a lot more ways to lay down a ship

such that there is a hit in a center square than there are ways to lay a

ship so that it gives a hit in a corner. In fact, for a particular ship

there are only two ways to lay it so that it registers a hit in the

corner. But, for a particular square in the center, for the Carrier for

example there are 5 different ways to lay it horizontally to register a

hit, and 5 ways to lay it vertically, or 10 ways total. Neat. We see

entropy in action.

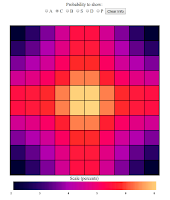

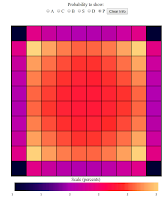

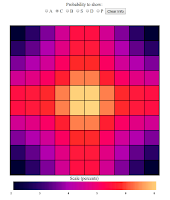

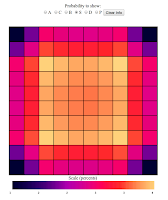

Carrier

Next let's look just at the Carrier:

Woah. This time the center is very heavily favored versus the edges.

This reflects the fact that the Carrier is a large ship, occupying 5

spaces, basically no matter how you lay it, it is going to have a part

that lies near the center.

Battleship

Now for the Battleship:

This is interesting. This time, the most probable squares are not the

center ones, but the not quite center ones. Why is that? Well, we saw

that for the Carrier, the probability of finding it in the center was

very large, and so respectfully, our battleship cannot be in the center

as often, as a lot of the time it would collide with the Carrier. Now,

this is not because I lay down the Carrier first, my board generation

algorithm assigns all of the boards at once, and just weeds out invalid

ones, this is a real entropic effect. So here we begin to see some

interesting Ship-Ship interactions in our probability distributions. But

notice again that on the whole, the battleship should also be found near

the center as it is also a large ship.

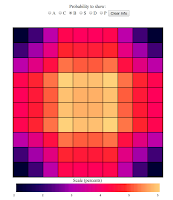

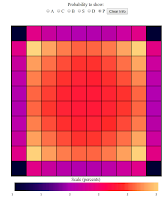

Sub / Destroyer

Next let's look at the sub / destroyer. First thing to note is that our

plot should be the same for both of these ships as they are both the

same length.

Here we see an even more pronounced effect near the center. The Subs and

Destroyers are 'pushed' out of the center because the Carriers and

Battleships like to be there. This is a sort of entropic repulsion.

Patrol Boat

Finally, let's look at the patrol boat:

The patrol boat is a tiny ship. At only two squares long, it can fit in

just about anywhere, and so we see it being strongly affected by the

affection the other ships have for the center. Neat stuff. So, we've

experimentally measured where we are likely to find all of the

battleship ships if we have a completely random board configuration.

Already we could use this to make our game play a little more effective,

but I think we can do better.

The Info

In fact, as a game of battleship unfolds, we learn a good deal of

information about the board. In fact on every turn we get a great deal

of information about a particular spot on the board, our guess. Can we

incorporate this information into our theory of battleship? Of course we

can, but first we need to come up with a good way to represent this

information. I suggest we invent another matrix! Let's call this one $$

I_{j,\beta} $$ Where I is for 'information', j goes from 0 to 99 and

beta marks the kind of information we have about a square, let's let it

take the values M,H,C,B,S,D,P, where M means a miss, H means a hit, but

we don't know which ship, and CBSDP mark a particular ship hit, which we

would know once we sink a ship. This matrix will be a binary one, where

for any particular value of j, the elements will all be 0 or 1, with

only one 1 sitting at the spot marking our information about the square,

if we have any. That was confusing. What do I mean? Well, let's say its

the start of the game and we don't know a darn thing about spot 34 on

the board, then I would set $$

I_{34,M}=I_{34,H}=I_{34,C}=I_{34,B}=I_{34,S}=I_{34,D}=I_{34,P}=0

$$ that is, all of the columns are zero because we don't have any

information. Now let's say we guess spot 34 and are told we missed, now

that row of our matrix would be $$ I_{34,M} = 1 \quad

I_{34,H}=I_{34,C}=I_{34,B}=I_{34,S}=I_{34,D}=I_{34,P}=0 $$ so that

we put a 1 in the column we know is right, instead, if we were told it

was a hit, but don't know which ship it was: $$ I_{34,H} = 1 \quad

I_{34,M}=I_{34,C}=I_{34,B}=I_{34,S}=I_{34,D}=I_{34,P}=0 $$ and

finally, lets say a few turns later we sink our opponents sub, and we

know that spot 34 was one of the spots the sub occupied, we would set:

$$ I_{34,S} = 1 \quad

I_{34,M}=I_{34,H}=I_{34,C}=I_{34,B}=I_{34,D}=I_{34,P}=0 $$ This

may seem like a silly way to codify the information, but I promise it

will pay off. As far as my Battleship Data

Explorer goes,

you don't have to worry about all this nonsense, instead you can just

click on squares to set their information content. Note: shift-clicking

will let you cycle through the particular ships, if you just regular

click it will let you shuffle between no information, hit, and miss.

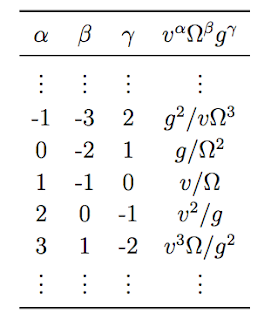

The Theory

Alright if we decide to go with my silly way of codifying the

information, at this point we have two pieces of data, $$ B_{i,\alpha}

$$ our background probability matrix, and $$ I_{j,\beta} $$ our

information matrix, where what we want is $$ P_{i,\alpha} $$ the

probability matrix. Here is where the linear part comes in. Why don't we

adopt the time honored tradition in science of saying that the

relationship between all of these things is just a linear one? In matrix

language that means we will choose our theory to be $$ P_{i,\alpha} =

B_{i,\alpha} + \sum_{j=[0,..,99],\beta={M,H,C,B,S,D,P}}

W_{i,\alpha,j,\beta} I_{j,\beta} $$ Whoa! What the heck is that!?

Well, that is my linear theory of battleship. What the equation is

trying to say is that I will try to predict the probability of a

particular ship being in a particular square by (1) noting the

background probability of that being true, and (2) adding up all of the

information I have, weighting it by the appropriate factor. So here, P

is our probability matrix, B is our background info matrix, I is our

information matrix, and W is our weight matrix, which is supposed to

apply the appropriate weights. That W guy seems like quite the monster.

It has four indexes! It does, so let's try to walk through what they all

mean. Here: $$ W_{i,\alpha,j,\beta} $$ is supposed to tell us: "the

extra probability of there being ship alpha at location i, given the

fact that we have the situation beta going on at location j" Read that

sentence a few times. I'm sorry its confusing, but it is the best way I

could come up with explaining W in english. Perhaps a visual would help.

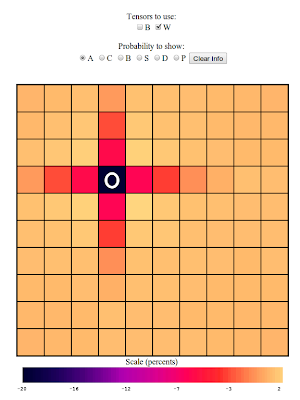

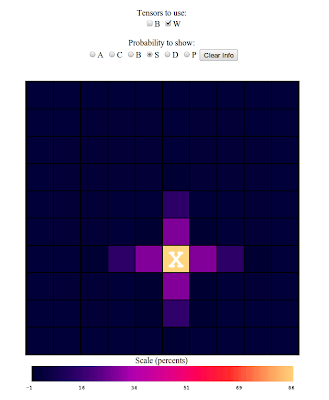

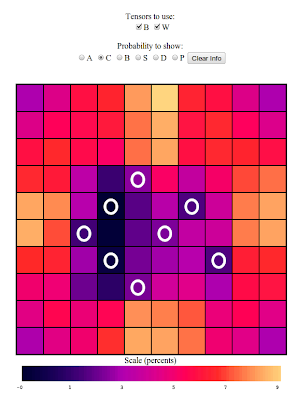

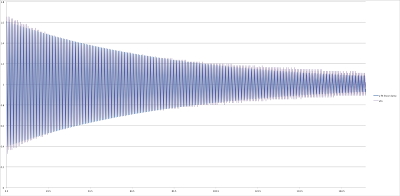

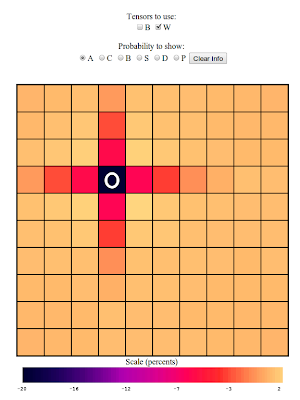

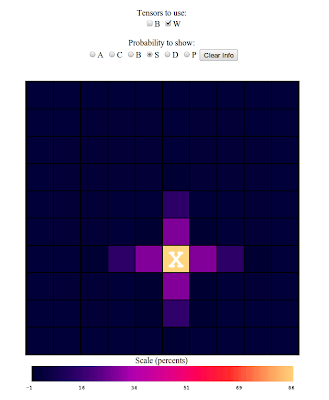

Behold the following: (click to embiggen)

That is a picture of $$ W_{i,C,33,M} $$ that is, that is a picture of

the extra probabilities for each square (i is all of them), of there

being a carrier, (alpha=C) given that we got a miss (beta=M) on square

33, (j=33). You'll notice that the fact that we saw a miss affects some

of the squares nearby. In fact, knowing that there was a miss on square

33 means that the probability that the carrier will be found on the

adjacent squares is a little lower (notice on the scale that the nearby

values are negative), because there are now fewer ways the carrier could

be on those squares without it overlapping over into square 33. Let's

try another:

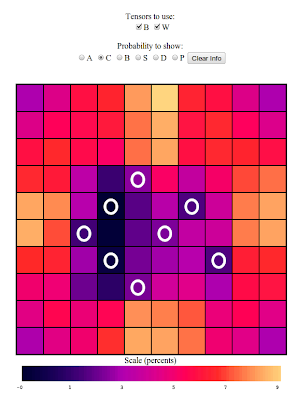

That is a picture of $$ W_{i,S,65,H} $$ that is, it's showing the extra

probability of there being a submarine (alpha=S), at each square (i is

all of them, since its a picture with 100 squares), given that we

registered a hit (beta=H) on square 65 (j=65). Here you'll notice that

since we marked a hit on square 65, it is very likely that we will also

get hits on the squares just next to this one, as we could have

suspected. In the end, by assuming our theory has this linear form, the

benefit we gain is that by doing the same sort of simulations I did to

generate the background information, I can back out what the proper

values should be for this W matrix. By doing billions and billions of

simulations, I can ask, for any particular set of information, I, what

the probabilities are P, and solve for W. Given that the problem is

linear, this solving step is particularly easy for me to do.

The Results

In the end, this is exactly what I did. I had my computer create

billions of different battleship boards, and figure out what the proper

values of B and W should be for every square of the matrix. I put all of

those results together in a way that I hope is easy to explore up at the

Fancy Battleship Results

Page, where you

are free to explore all of the results yourself. In fact, the way it's

set up, you can even use the Superduper Results

Page as a sort of

Battleship Cheat Sheet. Have it open while you play a game of

battleship, and it will show you the probabilities associated with all

of the squares, helping you make your next guess. I've used the page

while playing a few games of battleship online, and have had some

success, winning 9 of the 10 games I played against the computer player.

Of course, this linear theory isn't everything...

Why Linear isn't everything

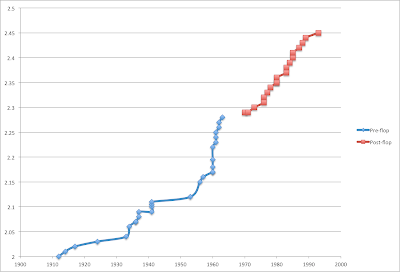

But at the end of the day, we've made a pretty glaring assumption about

the game of battleship, namely that all of the information on the board

adds in a linear way. Another way to say that is that in our theory of

battleship, we have a principle of superposition. Another way to say

that is that in this theory, what you think is happening in a particular

square is just the sum of the results from all of the squares,

independent of one another. Another way to say that is to show it with

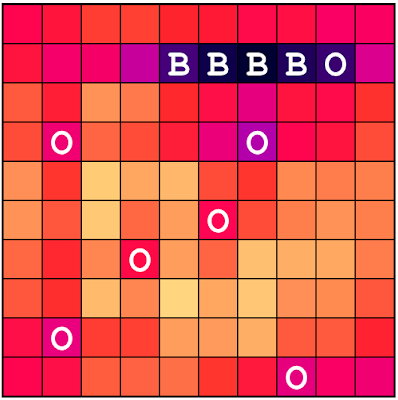

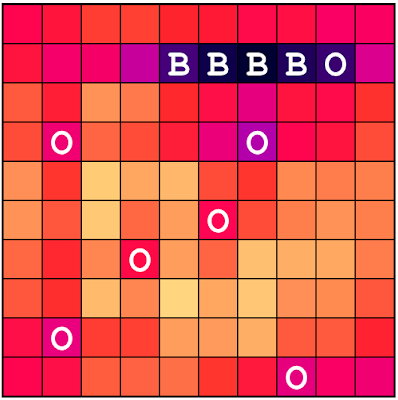

another picture. Consider the following:

Here, I've specified a bunch of misses, and am asking for the

probability of there being a Carrier on all of the positions of the

board. If you look in the center of that cluster of misses, especially

in the inner left of the bunch, you'll see that the linear theory tells

me that there is a small but finite chance that the Carrier is located

on those squares. But if you stop to look at the board a little bit,

you'll notice that I've arranged the misses such that there is a large

swatch of squares in the center of the cluster where the Carrier is

strictly forbidden. There is no way it can fit such that it touches a

lot of those central squares. This is an example of the failure of the

linear model. All the linear model knows is that in the spots nearby

misses there is a lower probability of the ship being there, but what it

doesn't know to do is look at the arrangement of misses and check to see

whether there is any possible way the ship can fit. This is a nonlinear

effect, involving information at more than one square at a time. It is

these kinds of effects that this theory will miss, but as you'll notice,

it still does pretty well. Even though it reports a finite positive

probability of the Carrier being inside the cluster, the value it

reports is a very small one, about 1 percent at most. So the linear

theory will have corrections at the 1 percent level or so, but that's

pretty good if you ask me.

Summary

And so it is. I've tried to develop a linear theory for the game

Battleship, and display the results in a Handy Dandy Data

Explorer. I

encourage you to play around with the website, use it to win games of

Battleship, and in the comments, point out interesting effects, things

you think I've missed, or ideas for how to come up with linear theories

of other things.

Marty McFly realizes he is running out of time to submit his solution

Marty McFly realizes he is running out of time to submit his solution