The Magnetar Credit Card Swipe

Ned Flanders' credit card doesn't satisfy the Luhn checksum, but could probably still be erased by a magnetar.

Ned Flanders' credit card doesn't satisfy the Luhn checksum, but could probably still be erased by a magnetar.

Hello, Internet! Today I'd like to talk about the Magnetar Credit Card Swipe. Sounds like some sinister short on a derivatives deal, doesn't it? Well, no need to worry, we don't deal with scary things like that here. Instead, we are going to talk about a super-magnetized neutron star speeding past Earth. A while ago I heard that a magnetar can erase all the world's credit cards from half the distance to the moon. I did a little research and it seems like this is the go-to "fun fact" about magnetars. Almost every time they are brought up in a popular science article, their credit card-erasing prowess is sure to get a mention. So let's check it out! First things first, though. What the heck is a magnetar [1]? Well, "magnetar" is just a spiffy name for a particular flavor of neutron star. Now, neutron stars are already pretty extreme objects. They've got a little more than the mass of the sun squished down to the size of a big city with a central density over 10 trillion times greater than lead.

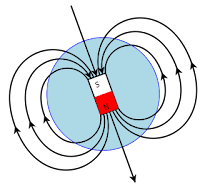

What makes magnetars truly name-worthy (and more extreme than Doritos and Mountain Dew at the X-Games) is the fact that they have strong magnetic fields. And when I say strong, I mean really strong. Taking the magnetic field to be dipolar (like the Earth's, see figure), the field at the poles of a magnetar can be as high as 10^15 gauss [2]. For comparison, the magnetic field of the Earth is about half a gauss and the big magnets used in MRIs are about 10^4 gauss. So we're talking about some big fields! Looking up the specs for a typical credit card, it looks like most take about 1000 gauss to erase. And now we can get started. I always forget the exact form of the magnetic field of a dipole, but Jackson doesn't. He tells me that it is $$ \vec{B}\left(\vec{r}\right) = \frac{3\vec{n}\left(\vec{n}\cdot\vec{m}\right) - \vec{m}}{|\vec{r} |^3}$$ where m is the magnetic dipole moment, r is the displacement vector to where we are measuring the field, and n is a unit vector that points to where we are measuring. To find the magnitude (which is what we really care about), we just take the dot product of the vector with itself and take the square root. Working this out we get $$ B\left(\vec{r}\right) = \frac{|\vec{m}|}{r^3}{\left[ 3\cos^2{\theta}+1\right]}^{1/2} $$ where theta is the angle between the magnetic moment vector and the direction vector n. But we are just looking for a rough estimate here so let's just set the cosine term to one. Now we have $$ B\left(r\right) = \frac{2|\vec{m}|}{r^3}$$ We can now use the above to our advantage. Since we are assuming we know the polar magnetic field strength, we can rearrange and solve for the magnetic moment. At the pole of a star the distance is just going to be the radius, so for radius R and field strength Bp, we get $$ |\vec{m}|} = \frac{1}{2}B_{p}R^3 $$ Plugging this back in, we get a nice little formula for the strength of the magnetic field in terms of the stellar radius and the polar field strength $$B(r) = B_{p}{\left(\frac{R}{r}\right)}^3 $$ And we are almost there! Rearranging now for r, we get $$r = R{\left[\frac{B_p}{B(r)}\right]}^{1/3} $$ Huzzah! Now we just need to plug in some values. Well, we'll use Bp = 10^15 gauss, B(r) = 1000 gauss (strong enough field to erase credit cards) and R = 10 km, which gives... $$ r \approx 10km \times {\left(\frac{10^{15}gauss}{10^{3}gauss}\right)}^{1/3} $$ so $$ r \approx \mbox{100,000 km} $$ The moon is about 380,000 km away. So we find that the magnetar will erase all credit cards up to a little over a quarter the distance to the moon. Not bad! However, all this talk of "half" and "quarter" is a bit misleading given that our best guesses here will be order of magnitude. But, overall, we see that a magnetar at roughly the Earth-Moon distance would have a good shot at erasing your credit cards. Fun fact confirmed! [1] For a really nice Scientific American article about magnetars, see here. For more information than you could probably ever want, see here. [2] For those of you who prefer your magnetic field strengths given in units named after someone played by David Bowie in a movie, you may note the conversion: 1 gauss = 10^-4 tesla.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus