Trigonometric Derivatives

I was recently reading The Endeavour where he responded to a post over at Math Mama Writes about teaching the derivatives of the trigonometric functions.

I decided to weigh in on the issue.

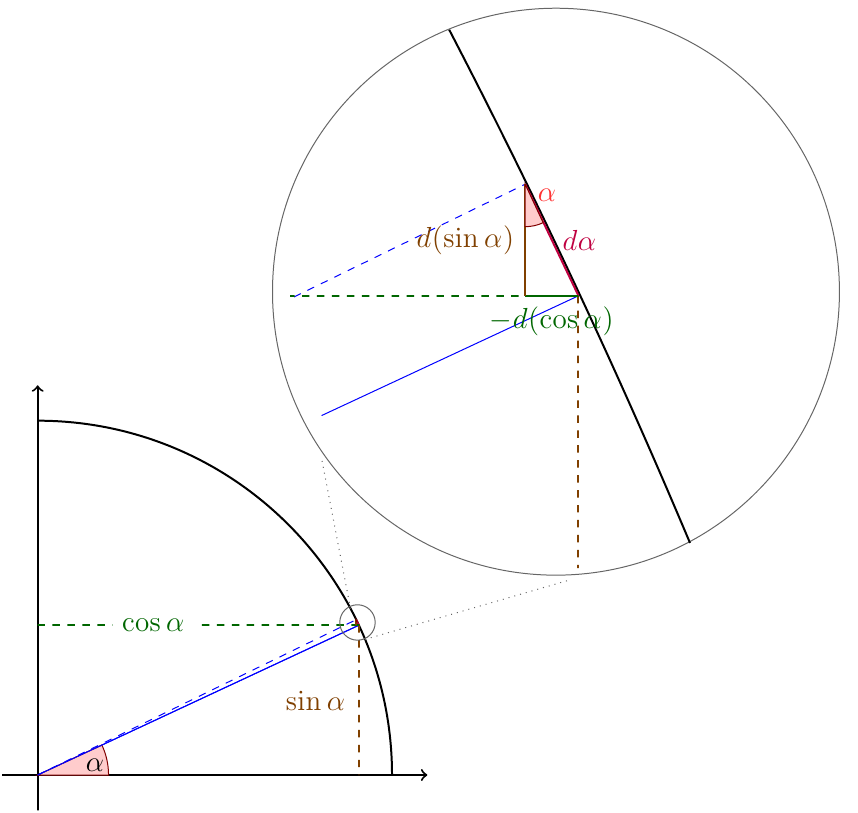

In my experience, Calculus is always best taught in terms of infinitesimals, as in Thompson's Book, (which I've already talked about ) and Trigonometry is best taught using the complete triangle. Marrying these two together, we can give a simple geometric proof of the basic trigonometric derivatives:

$$ \frac{ d }{dx } \sin x = \cos x \qquad \frac{d}{dx} \cos x = -\sin x $$

Summed up on one diagram:

Short version

By looking at how the line $\sin \alpha$ and $\cos \alpha$ change when we change $\alpha$ a little bit ($d\alpha$) and noting that we form a similar triangle, we know exactly what those lengths are.

Long version

You'll notice I've drawn a unit circle in the bottom right, chosen an angle $\alpha$, and shown both $\sin \alpha$ and $\cos \alpha$ on the plot.

We are interested in how $\sin \alpha$ changes when we make a very small change in $\alpha$, so I've done just that. I've moved the blue line from and angle of $\alpha$ to the dotted line at an angle of $\alpha + d\alpha$. Don't get caught up on the $d$ symbol here, it just means 'a little bit of'.

Since we've only moved the angle a little bit, I've included a zoomed in picture in the upper right so that we can continue. Here, we see the solid and dashed lines again where they meet our unit circle. Notice that since we've zoomed in quite a bit the circle's edge doesn't look very circley anymore, it looks like a straight line.

In fact that is the first thing we'll note, namely that the arc of the circle we trace when we change the angle a little bit has the length $d\alpha$. We know this is the case because we know that we've only gone an angle $d\alpha$, which is a small fraction $d\alpha/2\pi$ of the total circumference of the circle. The total circumference is itself $2\pi$ so at the end of the day, the length of that little bit of arc is just:

$$ \frac{ d\alpha }{2\pi} 2\pi = d\alpha $$

which we may have remembered anyway from our trig classes. What is important here is that even though $d \alpha$ is the length of the arc, when we are this zoomed in, we can treat the arc as a straight line. In fact if we imagine taking our change $d\alpha$ smaller and smaller, approximating the segment of arc as a line gets better and better. [Technically it should be noted that what is important is that the correction between the arc length and line length is higher order in $d\alpha$, so it can be ignored to linear order]

You'll notice that in the zoomed in picture, we can see the yellow and green segments, which correspond to the changes in the length of the dotted yellow and green segments from the zoomed out picture. These are the segments I've marked $d(\sin \alpha)$ and $-d(\cos \alpha)$, because the represent the change in the length of the $\sin \alpha$ line and $\cos \alpha$ line respectively. The green segment is marked $-d(\cos \alpha)$ because the $\cos \alpha$ line actually shrinks when we increase $\alpha$ a little bit.

Now for the kicker. Notice the right triangle formed by the green, yellow and red sements? That is similar to the larger triangle in the zoomed out picture. I've marked the similar angle in red. If you stare at the picture for a bit, you can convince yourself of this fact. If all else fails, just compute all of the angles involved in the intersection of the circle with the blue line, they can all be resolved.

Knowing that the two triangles are similar, we know that the lengths of theirs sides are equal except for some scale factor, in particular:

$$ \frac{ d(\sin \alpha) }{\cos \alpha} = \frac{ d\alpha }{ 1} $$

or

$$ d(\sin \alpha) = \cos \alpha \ d\alpha $$

And we've done it! Shown the derivative of $\sin \alpha$ with a little picture.

In particular, the change in the sine of the angle ($d(\sin \alpha)$) is equal to the cosine of that angle $\cos \alpha$ times the amount we change it. In the limit of very tiny angle changes, this tells us the derivative of $\sin \alpha$:

$$ \frac{d}{d\alpha} \sin \alpha = \cos \alpha $$

Doing the same for the $d(\cos \alpha)$ segment gives $$ d(\cos \alpha) = -\sin\alpha \ d\alpha $$ and we even get the sign right.

From here, the other trigonometric derivates are easy to obtain, either by making similar pictures al la the complete triangle, or by using the regular rules relating all of the trigonometric function to one another.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus