Solar Sails I

Solar sails are in the news again, and this time not just for blowing

up.

The Japanese space agency is

launching

what they hope to be the first successful solar sail tomorrow. In honor

of that, we will be discussing the physics of solar sails.

First of all, what the heck are solar sails? Solar sails are a means of

propulsion based on the simple observation that "Hey, sails work on

boats. Therefore, they should work on interplanetary spacecraft (in

space)." Boat sails work when air molecules hit into the sail and bounce

back. By conservation of momentum, this gives the boat sail an itty

bitty boost in momentum. Summing over the large number of air molecules

moving as wind, the boat gets pushed along in the water. A similar

process works with solar sails, but instead of air molecules doing the

hitting, it's photons. Since each photon of a given wavelength has some

momentum, by reflecting that photon the solar sail can gain a tiny bit

of momentum. Summing over the large number of photons coming from the

sun over a long time frame we can get a considerable boost. So let's see

how good solar sails are.

First we need to find the net force on our sail. We will certainly have

to deal with gravitational forces (which will slow us down) :

$$ F_{g} = \frac{-GM_{\odot}m}{r^2} $$

where big M is the mass of the sun and little m is the mass of the sail.

Now we need to find the radiation force on the sail. Since force is just

rate of change of momentum, we can find the change of momentum of one

photon per unit time, then find how many photons are hitting our sail.

So for one elastic collision of a photon with the sail, the change in

momentum will be

$$ \Delta p = 2 \frac{h\nu}{c} $$

and by conservation of momentum, this will also be the momentum gained

by the sail. Now we want to find the number of photons incident on a

given area in a given time. This will just be the energy flux output by

the sun ( energy/ m^2 s ) divided by the energy per photon. In other

words:

$$ f_n = \frac{L_{\odot}}{4\pi r^2}\frac{1}{h\nu} .$$

So now we can get a force by

$$ \text{Force} = \left(\frac{\Delta p}{\text{1 photon}} \right)

\times \left(\frac{\text{number of photons}}{area \times

time}\right) \times \left( Area\right) $$

which is just

$$ F_{rad} = 2 \frac{h\nu}{c} \times \frac{L_\odot}{4\pi r^2

h\nu} \times \pi R^2 = \frac{L_{\odot} R^2}{2cr^2} .$$

So combining the radiation force with the gravitation force, we have a

net force on the sail of

$$ F = \left( \frac{L_{\odot} R^2}{2c} - GM_{\odot}m \right)

\frac{1}{r^2} .$$

This can then be integrated over r to find an effective potential,

giving:

$$ U = \left( \frac{L_{\odot} R^2}{2c} -

GM_{\odot}m\right)\frac{1}{r} .$$

For simplicity, let's just write that

$$ \alpha = \frac{L_{\odot} R^2}{2c} - GM_{\odot}m $$

so

$$ U = \frac{\alpha}{r} .$$

Now we can start saying some things about this sail. The most

straightforward quantity to find would be the maximum velocity. By

conservation of energy (and starting from some r_0 at rest), we have

that

$$ v_f = \left[\frac{2\alpha}{m} \left(\frac{1}{r_0} -

\frac{1}{r_f} \right) \right]^{1/2} $$

So as r_f goes to very large values, the subtracted piece gets smaller

and smaller. In the limit that r_f goes to infinity we have that

$$ v_{max} = \left(\frac{2\alpha}{mr_0}\right)^{1/2} .$$

Plugging back in our long term for alpha and plugging in some numbers we

get:

$$ v_{max} = 42,000 m/s \left( \frac{1.5 \times 10^{-4}}{\sigma} -

1\right)^{1/2} $$

where sigma is just the surface mass density [g/cm^2] of the sail.

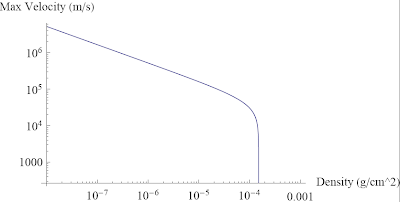

Below is a plot of maximum velocity ( m/s) plotted against surface mass

density (g/cm^2). For a sigma of 10^-4 g/cm^2, we get a max velocity

of about 30,000 m/s. Not bad.

Solar sails are in the news again, and this time not just for blowing

up.

The Japanese space agency is

launching

what they hope to be the first successful solar sail tomorrow. In honor

of that, we will be discussing the physics of solar sails.

First of all, what the heck are solar sails? Solar sails are a means of

propulsion based on the simple observation that "Hey, sails work on

boats. Therefore, they should work on interplanetary spacecraft (in

space)." Boat sails work when air molecules hit into the sail and bounce

back. By conservation of momentum, this gives the boat sail an itty

bitty boost in momentum. Summing over the large number of air molecules

moving as wind, the boat gets pushed along in the water. A similar

process works with solar sails, but instead of air molecules doing the

hitting, it's photons. Since each photon of a given wavelength has some

momentum, by reflecting that photon the solar sail can gain a tiny bit

of momentum. Summing over the large number of photons coming from the

sun over a long time frame we can get a considerable boost. So let's see

how good solar sails are.

First we need to find the net force on our sail. We will certainly have

to deal with gravitational forces (which will slow us down) :

$$ F_{g} = \frac{-GM_{\odot}m}{r^2} $$

where big M is the mass of the sun and little m is the mass of the sail.

Now we need to find the radiation force on the sail. Since force is just

rate of change of momentum, we can find the change of momentum of one

photon per unit time, then find how many photons are hitting our sail.

So for one elastic collision of a photon with the sail, the change in

momentum will be

$$ \Delta p = 2 \frac{h\nu}{c} $$

and by conservation of momentum, this will also be the momentum gained

by the sail. Now we want to find the number of photons incident on a

given area in a given time. This will just be the energy flux output by

the sun ( energy/ m^2 s ) divided by the energy per photon. In other

words:

$$ f_n = \frac{L_{\odot}}{4\pi r^2}\frac{1}{h\nu} .$$

So now we can get a force by

$$ \text{Force} = \left(\frac{\Delta p}{\text{1 photon}} \right)

\times \left(\frac{\text{number of photons}}{area \times

time}\right) \times \left( Area\right) $$

which is just

$$ F_{rad} = 2 \frac{h\nu}{c} \times \frac{L_\odot}{4\pi r^2

h\nu} \times \pi R^2 = \frac{L_{\odot} R^2}{2cr^2} .$$

So combining the radiation force with the gravitation force, we have a

net force on the sail of

$$ F = \left( \frac{L_{\odot} R^2}{2c} - GM_{\odot}m \right)

\frac{1}{r^2} .$$

This can then be integrated over r to find an effective potential,

giving:

$$ U = \left( \frac{L_{\odot} R^2}{2c} -

GM_{\odot}m\right)\frac{1}{r} .$$

For simplicity, let's just write that

$$ \alpha = \frac{L_{\odot} R^2}{2c} - GM_{\odot}m $$

so

$$ U = \frac{\alpha}{r} .$$

Now we can start saying some things about this sail. The most

straightforward quantity to find would be the maximum velocity. By

conservation of energy (and starting from some r_0 at rest), we have

that

$$ v_f = \left[\frac{2\alpha}{m} \left(\frac{1}{r_0} -

\frac{1}{r_f} \right) \right]^{1/2} $$

So as r_f goes to very large values, the subtracted piece gets smaller

and smaller. In the limit that r_f goes to infinity we have that

$$ v_{max} = \left(\frac{2\alpha}{mr_0}\right)^{1/2} .$$

Plugging back in our long term for alpha and plugging in some numbers we

get:

$$ v_{max} = 42,000 m/s \left( \frac{1.5 \times 10^{-4}}{\sigma} -

1\right)^{1/2} $$

where sigma is just the surface mass density [g/cm^2] of the sail.

Below is a plot of maximum velocity ( m/s) plotted against surface mass

density (g/cm^2). For a sigma of 10^-4 g/cm^2, we get a max velocity

of about 30,000 m/s. Not bad.

From this graph we see that there must be some maximum surface density,

above which we don't get any (forward) motion at all. This makes sense

since we want our radiation forces (which scale with area) to overcome

our gravitational forces (which scale with mass). And below this maximal

surface density we see a power law behavior. Cool.

We can also find the distance traveled as a function of time. Taking the

final velocity equation above and writing v as dr/dt, we see that

$$ \frac{dr}{dt} = \left[ \frac{2\alpha}{m} \left( \frac{1}{r_0}

- \frac{1}{r_f} \right)\right]^{1/2} $$

Rearranging and integrating, we can get time (in years) as a function of

distance r (in AU):

$$ t = \frac{0.11 \left(\sqrt{(-1+r)

r}+\text{Log}\left[1+\sqrt{\frac{-1+r}{r}}\right]+\frac{\text{Log}[r]}{2}\right)}{\sqrt{-1+\frac{1.5

\times 10^{-4}}{\sigma}}}$$

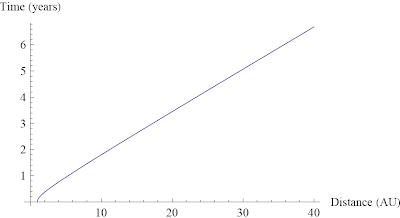

A plot of t vs. r is shown below for typical solar system distances and

a sigma of 10^-4 g/cm^2. We assume that we are launching from earth (1

AU). Since Pluto is at a distance of about 40 AU, we see that our sail

could get there in less than 7 years. For comparison, the New

Horizons probe will use conventional

propulsion to get to Pluto in 9.5 years (and it is the fastest

spacecraft ever made).

From this graph we see that there must be some maximum surface density,

above which we don't get any (forward) motion at all. This makes sense

since we want our radiation forces (which scale with area) to overcome

our gravitational forces (which scale with mass). And below this maximal

surface density we see a power law behavior. Cool.

We can also find the distance traveled as a function of time. Taking the

final velocity equation above and writing v as dr/dt, we see that

$$ \frac{dr}{dt} = \left[ \frac{2\alpha}{m} \left( \frac{1}{r_0}

- \frac{1}{r_f} \right)\right]^{1/2} $$

Rearranging and integrating, we can get time (in years) as a function of

distance r (in AU):

$$ t = \frac{0.11 \left(\sqrt{(-1+r)

r}+\text{Log}\left[1+\sqrt{\frac{-1+r}{r}}\right]+\frac{\text{Log}[r]}{2}\right)}{\sqrt{-1+\frac{1.5

\times 10^{-4}}{\sigma}}}$$

A plot of t vs. r is shown below for typical solar system distances and

a sigma of 10^-4 g/cm^2. We assume that we are launching from earth (1

AU). Since Pluto is at a distance of about 40 AU, we see that our sail

could get there in less than 7 years. For comparison, the New

Horizons probe will use conventional

propulsion to get to Pluto in 9.5 years (and it is the fastest

spacecraft ever made).

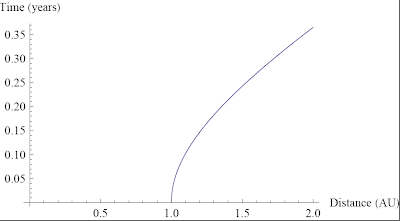

Zooming in to our starting point around 1 AU, we see that there is a

period of acceleration and then the maximum velocity is reached after a

few months. Just eyeballing it, it looks like it takes at least a month

to reach appreciable speed. That it takes so long is a result of the

very small forces involved due to radiation pressure. But even a small

acceleration amounts to a considerable speed if applied for long enough!

Zooming in to our starting point around 1 AU, we see that there is a

period of acceleration and then the maximum velocity is reached after a

few months. Just eyeballing it, it looks like it takes at least a month

to reach appreciable speed. That it takes so long is a result of the

very small forces involved due to radiation pressure. But even a small

acceleration amounts to a considerable speed if applied for long enough!

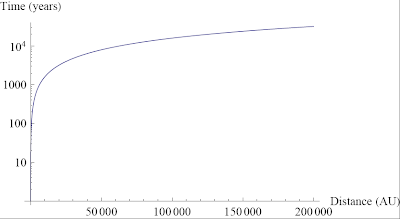

Now Pluto is fine I guess (it's the second largest dwarf-planet!), but

how about some interstellar flight? Well, the nearest star is Proxima

Centauri which is about a parsec away. A parsec is 310^16 m, or about

200,000 AU. From, the plot below (or plugging in to the equation above),

we see that such a trip would take of order 10,000 years. That's a long

time, but its not too shabby considering this craft uses no fuel of its

own.

Now Pluto is fine I guess (it's the second largest dwarf-planet!), but

how about some interstellar flight? Well, the nearest star is Proxima

Centauri which is about a parsec away. A parsec is 310^16 m, or about

200,000 AU. From, the plot below (or plugging in to the equation above),

we see that such a trip would take of order 10,000 years. That's a long

time, but its not too shabby considering this craft uses no fuel of its

own.

So solar sails can do some fairly impressive things simply by harnessing

the free energy of the sun. Though this only provides a very small

acceleration, it can be taken over a long enough time to be useful.

However, since the radiation pressure of the sun falls off as 1/r^2, we

start to observe diminishing returns and the sail reaches a max

velocity. But overall the numbers seem fairly impressive. All that

remains now is whether they are feasible to construct. Right now my only

data point for feasibility was that it was in Star

Wars, but as I

recall that was a long* time ago.

So solar sails can do some fairly impressive things simply by harnessing

the free energy of the sun. Though this only provides a very small

acceleration, it can be taken over a long enough time to be useful.

However, since the radiation pressure of the sun falls off as 1/r^2, we

start to observe diminishing returns and the sail reaches a max

velocity. But overall the numbers seem fairly impressive. All that

remains now is whether they are feasible to construct. Right now my only

data point for feasibility was that it was in Star

Wars, but as I

recall that was a long* time ago.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus