Ringing A Bridge

Matt and Jared standing on our experiment

Matt and Jared standing on our experiment

When you strike a bell, it rings at a given frequency. This frequency is

called the resonant frequency and is the natural frequency at which the

bell likes to ring. Just about anything that can shake, rattle, or

oscillate will have a resonant frequency. Things like quartz crystals,

wine glasses, and suspension bridges all have a resonant frequency. The

quartz crystals oscillate at frequencies high enough for accurate

timekeeping in watches, the wine glasses at audible frequencies to make

boring dinners more interesting, and bridges at low enough frequencies

that you can feel it when you walk. It is the resonant frequency of

bridges that we decided to measure.

To make our measurements, we "borrowed" Yariv's fancy phone. One of the

nice things about fancy new phones is that most of them have internal

accelerometers to detect motion. You can do a whole bunch of fun

experiments and take some pretty good data with these accelerometers

(see, for example, physicist and TV star Rhett Allain's posts over at

dot physics). Placing

Yariv's phone on the suspension footbridge on campus, Alemi, Matt and I

took data and confused passers-by for about 15 minutes. The

accelerometer in the phone measures acceleration in three coordinate

directions: x is along the width of the bridge, y is along the length of

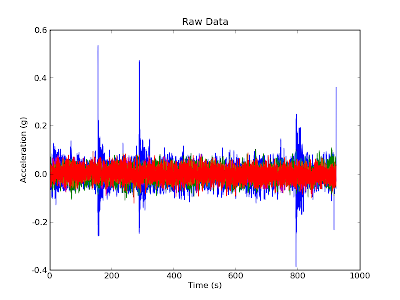

the bridge, and z is up and down. The raw data is shown below. The z

data is shown in blue, and x and y in green and red.

The first thing you'll notice about this data is that the z direction

(blue) has big spikes in it around 180s, 300s, and 800s. The biggest

spikes are when Alemi and I jumped up and down to ring the bridge. The

smaller bumps in the blue data are the result of people walking or

jogging by.

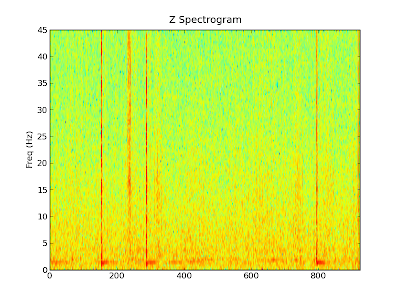

With the raw acceleration data and knowledge of the sample rate of the

accelerometer ( 90 Hz ), we can Fourier transform it to get frequencies.

Doing this to the raw data for each dimension we get the following

spectrograms. Each of the spectrograms illustrates how much of each

frequency is present at each point in time.

The most relevant direction for us is the z direction. We see that at

several points there are strong signals at all frequencies followed by

longer periods where the main signal is around 1 Hz. These events

correspond to when Alemi and I jumped up and down and are analogous to

ringing a bell. The striking of the bell is just a sharp impulse

(roughly a delta function) which is composed of all frequencies. Soon

after the impulse, all of the frequencies die out except for the

resonant frequency, which keeps on ringing. Just looking at this graph,

it looks like the bridge resonant frequency is around 1 Hz.

The first thing you'll notice about this data is that the z direction

(blue) has big spikes in it around 180s, 300s, and 800s. The biggest

spikes are when Alemi and I jumped up and down to ring the bridge. The

smaller bumps in the blue data are the result of people walking or

jogging by.

With the raw acceleration data and knowledge of the sample rate of the

accelerometer ( 90 Hz ), we can Fourier transform it to get frequencies.

Doing this to the raw data for each dimension we get the following

spectrograms. Each of the spectrograms illustrates how much of each

frequency is present at each point in time.

The most relevant direction for us is the z direction. We see that at

several points there are strong signals at all frequencies followed by

longer periods where the main signal is around 1 Hz. These events

correspond to when Alemi and I jumped up and down and are analogous to

ringing a bell. The striking of the bell is just a sharp impulse

(roughly a delta function) which is composed of all frequencies. Soon

after the impulse, all of the frequencies die out except for the

resonant frequency, which keeps on ringing. Just looking at this graph,

it looks like the bridge resonant frequency is around 1 Hz.

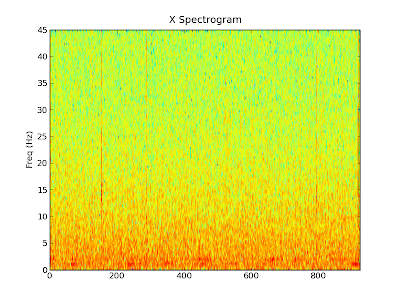

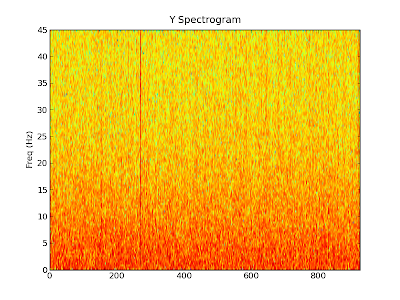

We can also make similar graphs for the x and y directions. Remember,

the x direction is the width of the bridge and the y direction is the

length of the bridge. Although there is less motion in these directions,

the spikes where we jumped and people walked by are still clearly

visible.

We can also make similar graphs for the x and y directions. Remember,

the x direction is the width of the bridge and the y direction is the

length of the bridge. Although there is less motion in these directions,

the spikes where we jumped and people walked by are still clearly

visible.

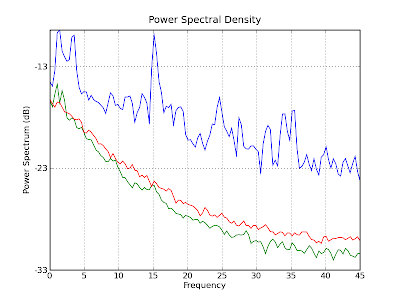

Finally, we can find out how much of a particular frequency is in the

whole signal. To do this we take find the power spectrum density of the

entire data set (blue is z, green is x and red is y). The ringdown

frequency of about 1 Hz we saw in the spectrograms above after the jumps

is illustrated in this graph as the first blue peak. There are also some

other peaks at around 15 Hz, 25 Hz and 35 Hz. I am not sure what they

correspond to.

Finally, we can find out how much of a particular frequency is in the

whole signal. To do this we take find the power spectrum density of the

entire data set (blue is z, green is x and red is y). The ringdown

frequency of about 1 Hz we saw in the spectrograms above after the jumps

is illustrated in this graph as the first blue peak. There are also some

other peaks at around 15 Hz, 25 Hz and 35 Hz. I am not sure what they

correspond to.

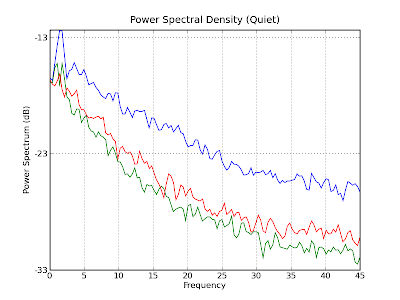

To clean up this a bit, we can just take the data without the jumps in

it. Computing a new power spectrum density with just the data from about

400s - 700s, we get the following graph, which also displays a fairly

prominent peak around 1 Hz.

To clean up this a bit, we can just take the data without the jumps in

it. Computing a new power spectrum density with just the data from about

400s - 700s, we get the following graph, which also displays a fairly

prominent peak around 1 Hz.

So it seems that there is definitely something going on around 1 Hz.

Initially, I was worried that this is just the rate at which people walk

and therefore it was just showing up because we had people walking the

whole time. However, the strong 1 Hz signal after each ringing in each z

spectrogram seems to indicate that it is intrinsic to the bridge.

Therefore, it seems as though the resonant frequency in the z direction

of the bridge is about 1 Hz. But don't take our word for it. If you want

to do your own analysis, you can find the raw data

here.

So it seems that there is definitely something going on around 1 Hz.

Initially, I was worried that this is just the rate at which people walk

and therefore it was just showing up because we had people walking the

whole time. However, the strong 1 Hz signal after each ringing in each z

spectrogram seems to indicate that it is intrinsic to the bridge.

Therefore, it seems as though the resonant frequency in the z direction

of the bridge is about 1 Hz. But don't take our word for it. If you want

to do your own analysis, you can find the raw data

here.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus