Pet Projects

Here at the Virtuosi, we have a very specific way of asking a very

specific type of question that sounds anything but specific. These are

the "How come [blank]?" questions [1]. These are very simple questions

that just about every four year old asks, but likely never get

sufficiently answered. To get a feel for what I mean by these questions

I provide the following translations of problems we have either

considered or will consider:

Q: How come trees?

Translation: How tall can trees be?

Q: How come plants?

Translation: Why are plants green?

These are my very favorite types of questions because they are

completely understandable by everyone and promise to have very

interesting physics working behind the scenes. So I've been thrilled to

see two such questions considered by scientists lately that have also

had a good run in popular media. They are:

Q: How come cats?

Translation: How do cats drink? and

Q: How come dogs?

Translation: How do dogs shake?

The question of how cats drink was

answered

recently by a few dudes from MIT, Virginia Tech and Princeton. One

morning, one of the guys was just watching his cat drink water and

realized he couldn't immediately figure out how it worked, so he decided

to do a bit more research and BAM! science happens.

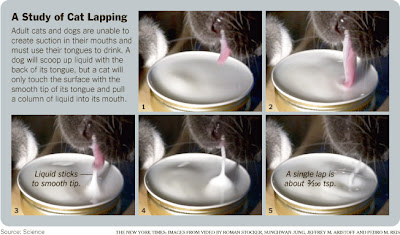

It turns out that the cat isn't just scooping up the water with it

tongue as one would probably have expected. Instead the cat uses its

tongue to effectively punch the water, drawing up a column of fluid.

They then bite this column and get a very itty bitty kitty mouthful of

water. Here it is in a slow motion video I stole from the Washington

Post who stole it from Reuters: (You'll probably have to sit through an

ad, apologies)

And here's a series of stills that illustrates the same thing:

Not a cat person? Well there was also a study done a month or so ago

about dog shaking. If you have a dog, you have almost certainly

experienced the elegant way in which a wet dog un-wettafies itself.

Well, a few students at Georgia Tech were also familiar with this

shaking and just happened to have a super high speed camera that could

track water droplets. I assume it only took a short period of time to

put two and two together and BAM! science happens. In addition to

providing the logical extension of the "spherical cow" joke to "dog of

radius R", the study also found some fairly surprising results. If we

are spinning a wet cylinder (i.e. dog), we would assume that the water

is held on by some "sticking force." Then to shake off these droplets,

we'd assume that the dog would have to shake fast enough that the

centrifugal force would overcome the sticking force. In other equations,

$$ F_{centrifugal} = m{\omega}^2 R $$ and $$ F_{sticking} = C $$ So

we would then expect the shaking frequency to be the frequency that gets

those two guys to equal each other. We would thus predict

$${\omega} \sim R^{-0.5} $$

where the little squiggle just means that the frequency scales as the

radius to the -0.5 power, with some constant multipliers out front that

we don't know so we just ignore.

But this is not what the Ga Tech guys observed! Check out the video

below:

So there's still something else going on that wasn't in our simple

model. But this is what makes science so exciting! Even something dogs

and cats figured out long ago can have some really rich and interesting

physics. So keep on asking those questions! Notes: [1] Interestingly

enough, the first "How come [blank]?" questions we asked did not have

the now canonical form. Instead, it was stated as "Why are cows?". After

much deliberation, we found that the solution is "Because milkshakes."

Fair enough.

Not a cat person? Well there was also a study done a month or so ago

about dog shaking. If you have a dog, you have almost certainly

experienced the elegant way in which a wet dog un-wettafies itself.

Well, a few students at Georgia Tech were also familiar with this

shaking and just happened to have a super high speed camera that could

track water droplets. I assume it only took a short period of time to

put two and two together and BAM! science happens. In addition to

providing the logical extension of the "spherical cow" joke to "dog of

radius R", the study also found some fairly surprising results. If we

are spinning a wet cylinder (i.e. dog), we would assume that the water

is held on by some "sticking force." Then to shake off these droplets,

we'd assume that the dog would have to shake fast enough that the

centrifugal force would overcome the sticking force. In other equations,

$$ F_{centrifugal} = m{\omega}^2 R $$ and $$ F_{sticking} = C $$ So

we would then expect the shaking frequency to be the frequency that gets

those two guys to equal each other. We would thus predict

$${\omega} \sim R^{-0.5} $$

where the little squiggle just means that the frequency scales as the

radius to the -0.5 power, with some constant multipliers out front that

we don't know so we just ignore.

But this is not what the Ga Tech guys observed! Check out the video

below:

So there's still something else going on that wasn't in our simple

model. But this is what makes science so exciting! Even something dogs

and cats figured out long ago can have some really rich and interesting

physics. So keep on asking those questions! Notes: [1] Interestingly

enough, the first "How come [blank]?" questions we asked did not have

the now canonical form. Instead, it was stated as "Why are cows?". After

much deliberation, we found that the solution is "Because milkshakes."

Fair enough.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus