Fun with an iPhone Accelerometer

The iPhone 3GS has a built-in accelerometer, the

LIS302DL,

which is primarily used for detecting device orientation. I wanted to

come up with something interesting to do with it, but first I had to see

how it did on some basic tests. It turns out that the tests gave really

interesting results themselves! A drop test gave clean results and a

spring test gave fantastic data; however a pendulum test gave some

problems. You might guess the accelerometer would give a reading of 0 in

all axes when the device is sitting on a desk. However, this

accelerometer measures "proper acceleration," which essentially is a

measure of acceleration relative to free-fall. So the device will read

-1 in the z direction (in units where 1 corresponds to 9.8 m/s^2, the

acceleration due to gravity at the surface of Earth). Armed with this

knowledge, let's take a look at the drop test: To perform this test, I

stood on the couch which was in my office (before it was taken away from

us!), and dropped my phone hopefully into the hands of my officemate. I

suspected that the device would read magnitude 1 before dropping, 0

during the drop, and a large spike for the large deceleration when the

phone was caught.

The iPhone 3GS has a built-in accelerometer, the

LIS302DL,

which is primarily used for detecting device orientation. I wanted to

come up with something interesting to do with it, but first I had to see

how it did on some basic tests. It turns out that the tests gave really

interesting results themselves! A drop test gave clean results and a

spring test gave fantastic data; however a pendulum test gave some

problems. You might guess the accelerometer would give a reading of 0 in

all axes when the device is sitting on a desk. However, this

accelerometer measures "proper acceleration," which essentially is a

measure of acceleration relative to free-fall. So the device will read

-1 in the z direction (in units where 1 corresponds to 9.8 m/s^2, the

acceleration due to gravity at the surface of Earth). Armed with this

knowledge, let's take a look at the drop test: To perform this test, I

stood on the couch which was in my office (before it was taken away from

us!), and dropped my phone hopefully into the hands of my officemate. I

suspected that the device would read magnitude 1 before dropping, 0

during the drop, and a large spike for the large deceleration when the

phone was caught.

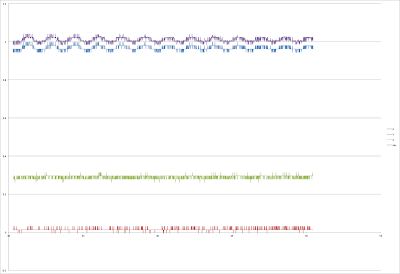

As you can see, the results were basically as expected. The purple line

shows the magnitude of the acceleration relative to free-fall. Before

the drop, the magnitude bounces around 1, which is due to my inability

to hold something steadily. The drop occurred near time 12.6, but I

wasn't able to move my hand arbitrarily quickly so there's not a sharp

drop to 0 magnitude. The phone fell for around 0.4 seconds corresponding

to $$y = \frac{1}{2} g t^2 = \frac{1}{2} (9.8 \frac{m}{s^2})(0.4

s)^2 = 0.784 m = 2.57 feet $$ As for the spike at 13 seconds, the raw

data shows that the catch occurs in $$ t = 0.02 \pm 0.01 s $$. In order

for the device to come to rest in such a short amount of time, there

needs to be a large deceleration provided by my officemate's hands. Now

the pendulum test consisted of taping my phone to the bottom of a 20

foot pendulum.

As you can see, the results were basically as expected. The purple line

shows the magnitude of the acceleration relative to free-fall. Before

the drop, the magnitude bounces around 1, which is due to my inability

to hold something steadily. The drop occurred near time 12.6, but I

wasn't able to move my hand arbitrarily quickly so there's not a sharp

drop to 0 magnitude. The phone fell for around 0.4 seconds corresponding

to $$y = \frac{1}{2} g t^2 = \frac{1}{2} (9.8 \frac{m}{s^2})(0.4

s)^2 = 0.784 m = 2.57 feet $$ As for the spike at 13 seconds, the raw

data shows that the catch occurs in $$ t = 0.02 \pm 0.01 s $$. In order

for the device to come to rest in such a short amount of time, there

needs to be a large deceleration provided by my officemate's hands. Now

the pendulum test consisted of taping my phone to the bottom of a 20

foot pendulum.

I didn't think enough about this, but the period of a pendulum, assuming

we have a small amplitude, is given by: $$T = 2 \pi

\sqrt{\frac{L}{g}}$$ which is about 5 seconds. With a relatively small

amplitude, the acceleration in the x direction will be small. Basically

I'm reaching the limit of the resolution of the acceleration device. It

appears that the smallest increment the device can measure is 0.0178 g.

This happens to match the specifications from the spec sheet I linked at

the top of the page, where they specify a minimum of 0.0162 g, and a

typical sensitivity of 0.018 g! Now we come to the most exciting test,

the spring test! Setup: I taped my phone to the end of a spring and let

it go. Ok. Here is the actual acceleration data:

I didn't think enough about this, but the period of a pendulum, assuming

we have a small amplitude, is given by: $$T = 2 \pi

\sqrt{\frac{L}{g}}$$ which is about 5 seconds. With a relatively small

amplitude, the acceleration in the x direction will be small. Basically

I'm reaching the limit of the resolution of the acceleration device. It

appears that the smallest increment the device can measure is 0.0178 g.

This happens to match the specifications from the spec sheet I linked at

the top of the page, where they specify a minimum of 0.0162 g, and a

typical sensitivity of 0.018 g! Now we come to the most exciting test,

the spring test! Setup: I taped my phone to the end of a spring and let

it go. Ok. Here is the actual acceleration data:

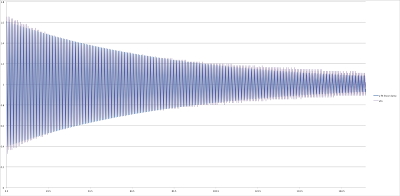

The first thing I see is that the oscillation frequency looks constant,

as it should be for a simple harmonic oscillator. There is also a decay

which looks exponential! Let's see how well the data fits if we have a

frictional term proportional to the velocity of the phone. This gives is

a differential equation which looks like this: $$ m \ddot{x} +

F\dot{x} + k x = 0 $$ Now we can plug in an ansatz (educated guess) to

solve this equation: $$ x(t) = Ae^{i b t} $$ $$-b^2 mx(t) + i b

Fx(t) + kx(t) = 0$$ $$-m b^2+iFb+k = 0$$ We can solve this equation for

b with the quadratic equation: $$ b = \frac{\sqrt{4km - F^2}}{2m} +

i\frac{F}{2m} \equiv \omega + i \gamma $$ where I defined two new

constants here. So we see that our ansatz does solve the differential

equation. Now we want acceleration, which is the second time derivative

of position with respect to time. $$a(t) \equiv \ddot{x} = -b^2 A

e^{ibt} $$ Now are only interested in the real part of this solution,

which gives us (adding in a couple of constants to make the solution

more general): $$a(t) = -(\omega^2 - \gamma^2) A e^{-\gamma t}

cos(\omega t + \phi) + C $$ Let's redefine the coefficient of this

acceleration to make things a little cleaner! $$a(t) = B e^{-\gamma t}

cos(\omega t + \phi) + C $$ Ok, with that math out of the way (for

now), we can try to fit this data. I actually used Excel to fit this

data using a not-so-well-known tool called Solver. This allows you to

maximize or minimize one cell while Excel varies other cells. In this

case, I defined a cell which is the Residual Sum of

Squares of my fit

versus the actual data, and I tell Excel to vary the 5 constants which

make the fit! The values jump around for a little while then it gives up

when it thinks it converged to a solution. Using this you can fit

arbitrary functions, neato! With this, I come up with the following

plot:

The first thing I see is that the oscillation frequency looks constant,

as it should be for a simple harmonic oscillator. There is also a decay

which looks exponential! Let's see how well the data fits if we have a

frictional term proportional to the velocity of the phone. This gives is

a differential equation which looks like this: $$ m \ddot{x} +

F\dot{x} + k x = 0 $$ Now we can plug in an ansatz (educated guess) to

solve this equation: $$ x(t) = Ae^{i b t} $$ $$-b^2 mx(t) + i b

Fx(t) + kx(t) = 0$$ $$-m b^2+iFb+k = 0$$ We can solve this equation for

b with the quadratic equation: $$ b = \frac{\sqrt{4km - F^2}}{2m} +

i\frac{F}{2m} \equiv \omega + i \gamma $$ where I defined two new

constants here. So we see that our ansatz does solve the differential

equation. Now we want acceleration, which is the second time derivative

of position with respect to time. $$a(t) \equiv \ddot{x} = -b^2 A

e^{ibt} $$ Now are only interested in the real part of this solution,

which gives us (adding in a couple of constants to make the solution

more general): $$a(t) = -(\omega^2 - \gamma^2) A e^{-\gamma t}

cos(\omega t + \phi) + C $$ Let's redefine the coefficient of this

acceleration to make things a little cleaner! $$a(t) = B e^{-\gamma t}

cos(\omega t + \phi) + C $$ Ok, with that math out of the way (for

now), we can try to fit this data. I actually used Excel to fit this

data using a not-so-well-known tool called Solver. This allows you to

maximize or minimize one cell while Excel varies other cells. In this

case, I defined a cell which is the Residual Sum of

Squares of my fit

versus the actual data, and I tell Excel to vary the 5 constants which

make the fit! The values jump around for a little while then it gives up

when it thinks it converged to a solution. Using this you can fit

arbitrary functions, neato! With this, I come up with the following

plot:

$$B = 0.633740943$$ $$\gamma = 0.012097581 $$ $$\omega = 8.599670376

$$ $$\phi = 0.693075811 $$ $$C =-1.004454967 $$ with an R^2 value of

0.968! At this point it should be noted that if I discretize my smooth

fit to have the same resolution (0.0178 g) as the accelerometer, then

see what the error is comparing the smooth fit to its own

discretization, I get an R^2 of 0.967! This means that there is a

decent amount of built-in error to these fits due to discretization on

the order of the error we're seeing for our actual fits. Immediately we

can recognize that C should be -1, since this is just a factor relating

"free-fall" acceleration to actual iPhone acceleration. If we wanted, we

could solve for the ratio of the spring constant to the mass, but I'll

leave that as an exercise for the

reader.

If you look closely, you can see that the frequency appears to match

very well. The two lines don't go out of phase. One problem with the fit

is the decay. The beginning and the end of the data are too high

compared to the fit, which is a problem. This implies that there is some

other kind of friction at work. Some larger objects or faster moving

objects tend to experience a frictional force proportional to the square

of the velocity. I don't think my iPhone is large or fast (compared to a

plane for example), but I'll try it anyway. The differential equation

is: $$ m \ddot{x} + F\dot{x}^2 + k x = 0 $$ yikes. This is a tough

one because of the velocity squared term. One trick I found

here attempts a general solution for

a similar equation. They make an approximation in order to solve it, but

the approximation is pretty good in our case. Take a look at the paper

if you're interested. The basic idea is to note that the friction term

is the only one that affects the energy. So, assuming that the energy

losses are small in a cycle, we can look at a small change in energy

with respect to a small change in time due to this force term. This

gives us an equation which can let us solve for the amplitude as a

function of time approximately! Really interesting idea. So I plugged

the following equation into the Excel Solver: $$a(t) = \frac{A

cos(\omega t + \phi)}{\gamma t + 1} + B$$ Here's the fit:

$$B = 0.633740943$$ $$\gamma = 0.012097581 $$ $$\omega = 8.599670376

$$ $$\phi = 0.693075811 $$ $$C =-1.004454967 $$ with an R^2 value of

0.968! At this point it should be noted that if I discretize my smooth

fit to have the same resolution (0.0178 g) as the accelerometer, then

see what the error is comparing the smooth fit to its own

discretization, I get an R^2 of 0.967! This means that there is a

decent amount of built-in error to these fits due to discretization on

the order of the error we're seeing for our actual fits. Immediately we

can recognize that C should be -1, since this is just a factor relating

"free-fall" acceleration to actual iPhone acceleration. If we wanted, we

could solve for the ratio of the spring constant to the mass, but I'll

leave that as an exercise for the

reader.

If you look closely, you can see that the frequency appears to match

very well. The two lines don't go out of phase. One problem with the fit

is the decay. The beginning and the end of the data are too high

compared to the fit, which is a problem. This implies that there is some

other kind of friction at work. Some larger objects or faster moving

objects tend to experience a frictional force proportional to the square

of the velocity. I don't think my iPhone is large or fast (compared to a

plane for example), but I'll try it anyway. The differential equation

is: $$ m \ddot{x} + F\dot{x}^2 + k x = 0 $$ yikes. This is a tough

one because of the velocity squared term. One trick I found

here attempts a general solution for

a similar equation. They make an approximation in order to solve it, but

the approximation is pretty good in our case. Take a look at the paper

if you're interested. The basic idea is to note that the friction term

is the only one that affects the energy. So, assuming that the energy

losses are small in a cycle, we can look at a small change in energy

with respect to a small change in time due to this force term. This

gives us an equation which can let us solve for the amplitude as a

function of time approximately! Really interesting idea. So I plugged

the following equation into the Excel Solver: $$a(t) = \frac{A

cos(\omega t + \phi)}{\gamma t + 1} + B$$ Here's the fit:

Which uses these values: $$A = 0.772773705 $$ $$\gamma = 0.029745368 $$

$$\omega = 8.600177692 $$ $$\phi = 0.688610161 $$ $$B = -1.004530009

$$ with an R^2 value of 0.964! This fit seems to have the opposite

effect. The middle of the data is too high compared to the fit, while

the beginning and end of the data seems too low. This makes me think

that the actual friction terms involved in this problem are possibly a

sum of a linear term and a squared term. I don't know how to make

progress on that differential equation, so I wasn't able to fit

anything. If you try the same trick I mentioned earlier, you run into a

problem where you can't separate some variables which you need to

separate in the derivation unfortunately. So there you have it, I wanted

to find something neat to do, and I got really cool data from just

testing the accelerometer. Stay tuned for an interesting challenge

involving some physical data from my accelerometer!

Which uses these values: $$A = 0.772773705 $$ $$\gamma = 0.029745368 $$

$$\omega = 8.600177692 $$ $$\phi = 0.688610161 $$ $$B = -1.004530009

$$ with an R^2 value of 0.964! This fit seems to have the opposite

effect. The middle of the data is too high compared to the fit, while

the beginning and end of the data seems too low. This makes me think

that the actual friction terms involved in this problem are possibly a

sum of a linear term and a squared term. I don't know how to make

progress on that differential equation, so I wasn't able to fit

anything. If you try the same trick I mentioned earlier, you run into a

problem where you can't separate some variables which you need to

separate in the derivation unfortunately. So there you have it, I wanted

to find something neat to do, and I got really cool data from just

testing the accelerometer. Stay tuned for an interesting challenge

involving some physical data from my accelerometer!

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus