Betelgeuse, Betelgeuse, Betelgeuse!

A very cold person points out Betelgeuse

A very cold person points out Betelgeuse

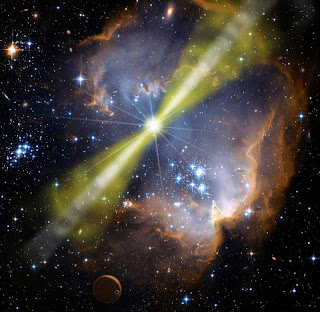

Betelgeuse is a massive star at the very end of its life and could explode any second now! Every time I hear that I get really really excited. Like a kid in a candy store that's about to see a star blow up like nobody's business. This giddiness will last for a solid minute before I realize that "any second now" is taken on astronomical timescales and roughly translates to "sometime in the next million years maybe possibly." Then I feel sad. But you know what always cheers me up? Calculating things! Hooray! So let's take a look at the ways Betelgeuse could end its life (even if it's not going to happen tomorrow) and how these would affect Earth. First, a little background. Betelgeuse is the bright orangey-red star that sits at the head/armpit of Orion. It is one of the brightest stars in the night sky. Its distance has been measured by the Hipparcossatellite to be about 200 parsecs [1] from Earth (about 600 light years). Betelgeuse is at least 10 times as massive as our Sun and has a diameter that would easily accomodate the orbit of Mars. In fact, the star is big enough and close enough that it can actually be spatially resolved by the Hubble Space Telescope! Being so big and bright, Betelgeuse is destined to die young, going out with a bang as a core-collapse supernova. This massive explosion ejects a good deal of "star stuff" into interstellar space [2] and leaves behind either a neutron star or a black hole. Alright, now that we're all caught up, let's turn our focus on this "massive explosion" bit. What kind of energy scale are we talking about if Betelgeuse blows up? Well, a pretty good upper bound would be if all of the star's mass (10 solar masses worth!) were converted directly to energy, so $$ E_{max} = mc^2 = 10M_{\odot}\times\left(\frac{2\times10^{30}\~\mbox{kg}}{1\~M_{\odot}}\right)\times \left(3\times10^8\~\mbox{m/s}\right)^2 $$ which is about $$ E_{max} \sim 10^{48}\~\mbox{J} $$ and that's nothing to shake a stick at. But remember, this is if the entire star were converted directly to energy, and that would be hard to do. Typical fusion efficiencies are about \~1% [3], so let's say a reasonable estimate for the total nuclear energy available is $$ E_{nuc} \sim \eta_{f} \times E_{max} \sim 10^{-2} \times 10^{48}\~\mbox{J} \sim 10^{46}\~\mbox{J}. $$ This is the total energy released by a typical supernova. As it turns out though, 99% of this energy is carried away in the form of neutrinos and only about 1% is carried away in photons. Since we are mainly concerned with how this explosion will affect Earth, and the neutrinos will just pass on by, we will only consider the 1% of energy released in photons that would reasonably interact with Earth. That gives us $$ E_{ph} \sim 0.01 \times E_{nuc} \sim 10^{44}\~\mbox{J}. $$ Neato, so that's the total amount of energy released in a supernova in the form of photons. How much of this energy would be deposited at the Earth if Betelgeuse exploded? Well, if the energy is deposited isotropically (that is, the same in all directions), then the fluence (or time integrated energy flux) is given by $$ F_{ph} = \frac{E_{ph}}{4\pi d^2}. $$ All this is saying is that the total energy release by the supernova spreads out uniformly over a sphere of radius d, so the fluence will give us the amount of energy deposited in each square meter of that sphere (the units of fluence here are J/m^2). The total energy deposited on Earth is then $$ E_{\oplus} = F_{ph} \times \pi R^2_{\oplus}. $$ Hot dog! Let's plug in some numbers, already. The total energy deposited on the Earth by a symmetrically exploding Betelgeuse at a distance of d = 200 pc (where 1 pc = 3 10^16 m) is $$E_{\oplus}=\frac{E_{ph}}{4\pi d^2}\times\pi R^2_{\oplus}\sim 10^{19}\~\mbox{J}\left(\frac{E_{ph}}{10^{44}\~\mbox{J}}\right)\left(\frac{d}{200\~\mbox{pc}}\right)^{-2}.$$ Well, 10^19 J certainly seems* like a lot of energy. In fact, it is roughly the amount of energy contained in the entire nuclear arsenal of the United States [4]. But it is spread over the entire atmosphere. Is there a way to gauge how this would affect life on Earth? We could see how much it would heat up the atmosphere using specific heats: $$ E = m_{atm}c_{air}\Delta T $$ where c is the specific heat of air (\~10^3 J per kg per K). Oops, looks like we need to know the mass of the atmosphere. But we can figure this out, the answer is pushing right down on our heads! We know the pressure at the surface of the Earth (1 atm = 101 kPa) and that pressure is just the result of the weight of the atmosphere pushing down on us. Since pressure is just force / area, we have $$ P = F/A = m_{atm}g / A_{\oplus} $$ So $$ m_{atm} = \frac{P\times4\pi R^2_{\oplus}}{g}=\frac{10^5\~\mbox{Pa}\times4\pi (6\times10^6\~\mbox{m})^2}{9.8\~\mbox{m/s}^2}\approx4\times10^{18}\~\mbox{kg}.$$ Neato, gang. So we could see a temperature rise of about $$ \Delta T = \frac{E_{ph}}{m_{atm}c_{air}}=\frac{10^{19}\~\mbox{J}}{4\times10^{18}\~\mbox{kg}\times10^3\~\mbox{J/ kg K}}\approx0.003\~\mbox{K}, $$ or three one-thousandths of a degree. Remember, too, that this will be an upper bound since we are assuming that all this energy is deposited into the atmosphere before it has a chance to cool. In fact, if the energy is deposited over the course of hours or days, this value will be much less. So it looks like we've wrapped this thing up: Betelgeuse exploding will most certainly not put the Earth in any danger. Or did we? We have considered the case of a symmetric supernova, but there's more than one way to blow up a star. Massive stars can also end their lives in a fantastic explosion called a gamma-ray burst (GRBs to the hep cats that study them, some fun facts relegated to [5]). GRBs are still an intense area of current study, but the current picture (for one type of GRB, at least) is that they are the result of a star blowing up with the energy of the explosion focussed into two narrow beams (see picture below). Since the flux isn't distributed over the whole sphere, GRBs can be seen at much greater distances than a typical supernova.

Example of a gamma-ray burst, with the explosion in two beams.

Example of a gamma-ray burst, with the explosion in two beams.

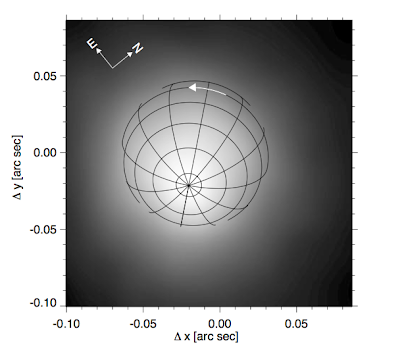

So how will this change our answer? Well, it's going to change the fluence we calculated above. Instead of spreading the energy out over the whole sphere, it's only going to go to some fraction of the 4pi steradians. So we get $$ F_{ph} = \frac{E_{ph}}{4\pi f_{\Omega} d^2}, $$ where f_{omega} is called the "beaming fraction" and tells us what fraction of the sphere the energy goes through. Typical GRB beams range from 1 to 10 degrees in radius. Converting this to radians, we can find the beaming fraction as $$ f_{\Omega} = \frac{2 \times \pi \theta^2}{4\pi} \approx 10^{-4}\left(\frac{\theta}{1^\circ}\right)^2,$$ so the beaming fraction is 10^-4 and 10^-2 for a beam angle of 1 degree and 10 degrees, respectively. Alright, so now we can redo the calculations we did for the supernova case, but keeping this beaming fraction around. The total amount of energy that would hit Earth is then about $$E_{\oplus}=\frac{E_{ph}}{4\pi f_{\Omega} d^2}\times\pi R^2_{\oplus}\sim 10^{23}\~\mbox{J}\left(\frac{E_{ph}}{10^{44}\~\mbox{J}}\right)\left(\frac{d}{200\~\mbox{pc}}\right)^{-2}\left(\frac{\theta}{1^\circ}\right)^{-2}.$$ Holy sixth-of-a-moley! Continuing as we did above, we find that this could potentially heat up the atmosphere by $$ \Delta T = \frac{E_{ph}}{m_{atm}c_{air}}=\frac{10^{23}\~\mbox{J}}{4\times10^{18}\~\mbox{kg}\times10^3\~\mbox{J/ kg K}}\approx3\~\mbox{K}\left(\frac{\theta}{1^\circ}\right)^{-2}, $$ which is certainly non-negligible. Now, this won't destroy the planet [6], but it could make things really uncomfortable. This will be especially true when you realize that a fair amount of the energy carried away from a gamma-ray burst is in the form of (wait for it...) gamma-rays, which will wreck havoc on your DNA. Remember, though, that this is an absolute worst-case scenario since we have assumed the smallest beaming angle. But this may still make us a little nervous, so is there anyway to figure out if Betelgeuse could, in fact, beam a gamma-ray burst towards Earth? Yes, yes there is. Jets and beams like those in GRBs typically point along the rotation axis of the star [7]. If we could determine the rotational axis of Betelgeuse, then we could say whether or not there's a chance it's pointed towards us. It just so happens that Betelgeuse is the only star (aside from our Sun) that is spatially resolved. If you could measure spectra along the star, you could look for Doppler shifting of absorption lines and say something about the velocity at the surface of the star. Luckily, this has already been done for us (see, for example Uitenbroek et al. 1998). These measurements are hard to do since the star is only a few pixels wide, but it appears as though the rotation axis is inclined to the line-of-sight by about 20 degrees (see figure below). That means this would require a beam with at least a 20 degree radius to hit the Earth. This appears to be outside the typical ranges observed. So even if Betelgeuse were to explode in a gamma-ray burst, the beam would miss Earth and hit some dumb other planet nobody cares about.

Figure reproduced from Uitenbroek et al. (1998)

Figure reproduced from Uitenbroek et al. (1998)

Alright, so the moral of the story is that Betelgeuse is completely harmless to people on Earth. When it does explode, it will be a brilliant supernova that would likely be visible at least a little bit during the day. It will be the coolest thing that anyone alive (if there are people...) will ever see. Sadly, this explosion could take place at just about any time during the next million years. Assuming a uniform distribution over this time period and a human lifetime of order 100 years, there is something like a 1 in 10,000 chance you'll see this in your life. Feel free to hope for a spectacular astronomical sight, but don't lose sleep worrying about being hurt by Betelgeuse! Semi-excessive Footnotes: [1] This has nothing to do with the Kessel Run. For a description of the actual distance unit see Wikipedia. For a circuitous retconning to correct for one throwaway line in Star Wars, see Wookieepedia. [2] This is how anything heavier than helium gets distributed throughout the universe. The hydrogen and helium formed after the Big Bang gets fused into heavier elements in stars and then dispersed out through supernovae. In fact, most things heavier than Iron actually require supernovae to even exist. If you have any gold on you right now (I'm looking at you Mr. T), that only exists because a star exploded! [3] Let's consider the case of turning 4 protons into a Helium nucleus. Helium-4 has a binding energy of about 28 MeV, which means that the total energy of a bound He-4 nucleus is 28 MeV less than its free protons and neutrons (in other words, we need to put in 28 MeV to break it up). So the process of turning 4 protons into a Helium nucleus gives off 28 MeV worth of energy. But we had a total of 4 times 1000 MeV worth of matter we could have turned into energy. Thus, the process was 28 MeV/4000 MeV \~ 0.7% efficient at turning matter into energy. [4] Sometime last year, the United States disclosed that its nuclear arsenal as of Sept 2009 was something like 5000 warheads. Assume these to be Megaton warheads. A Megaton is about 4 10^15 J, so the total energy in the US arsenal is about 5000 * 4 10^15 J = 2 * 10^19 J. [5] A fun fact about GRBs: They were discovered by a military satellite looking for illegal nuclear tests, which would emit some gamma-rays. Instead of seeing a signal on Earth, they saw bursts coming from space. I really really hope that someone's first thought was that the Russians were testing nukes on the Moon or something. We must not allow a moon-nuke gap! [6] We here at the Virtuosi are contractually obligated to only destroy the Earth in our posts on Earth day. I apologize for any inconvenience this may cause. [7] I am not exactly sure why this is the case. It is certainly observed to be the case and I thought there was a straightforward explanation for why this was the case, but I don't really have a good explanation. Although, maybe there just isn't a good one yet. [8] For comparison, there is about a 1 in 3000 chance you'll be struck by lightning in your lifetime.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus