Benford's Law

Given a large set of data (bank accounts, river lengths, populations,

etc) what is the probability that the first non-zero digit is a one? My

first thought was that it would be 1/9. There are nine non-zero numbers

to choose from and they should be uniformly distributed, right? Turns

out that for almost all data sets naturally collected, this is not the

case. In most cases, one occurs as the first digit most frequently, then

two, then three, etc. That this seemingly paradoxical result should be

the case is the essence of Benford's Law. Benford's Law [1] states that

for most real-life lists of data, the first significant digit in the

data is distributed in a specific way, namely: $$ P(d) =

\mbox{log}{10}\left(1 + \frac{1}{d}\right) $$ The probabilities

for leading digits are roughly P(1) = 0.30, P(2) = 0.18, P(3) = 0.12,

P(4) = 0.10, P(5) = 0.08, P(6) = 0.07, P(7) = 0.06, P(8) = 0.05, P(9) =

0.04. So we would expect the first significant digit to be a one almost

30% of the time! But where would such a distribution come from? Well, it

turns out that it comes from a distribution that is logarithmically

uniform. We can map the interval [1,10) to the interval [0,1) by just

taking a logarithm (base ten). These logarithms are then distributed

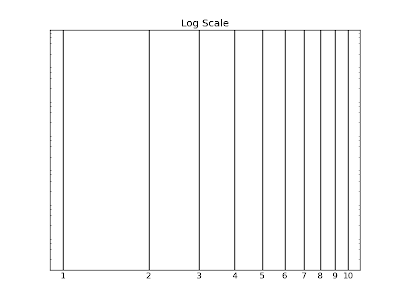

uniformly on the interval [0,1). We can now get some grasp for why one

should occur as the first digit more often in a uniform log

distribution. In the figure below, I have plotted 1-10 on a logarithm

scale. In a uniform log distribution, a given point is equally likely to

be found anywhere on the line. So the probability of getting any

particular first digit is just its length along that line. Clearly, the

intervals get smaller as the numbers get bigger.

But we can quantify this, too. For a first digit on the interval [1,10),

the probability that the first digit is d is given by:

$$ P(d) = \frac{\mbox{log}(d+1)

-\mbox{log}{10}(d)}{\mbox{log}(10) -\mbox{log}{10}(1)} $$

which is just $$ P(d) =\mbox{log}(d+1) -\mbox{log}{10}(d) $$

or $$ P(d) = \mbox{log}\left( 1 + \frac{1}{d} \right) $$ which

is the distribution of Benford's Law. So how well do different data sets

follow Benford's Law? I decided to test it out on a couple easily

available data sets: pulsar periods, U.S. city populations, U.S. county

sizes and masses of plant genomes. Let's start first with pulsar

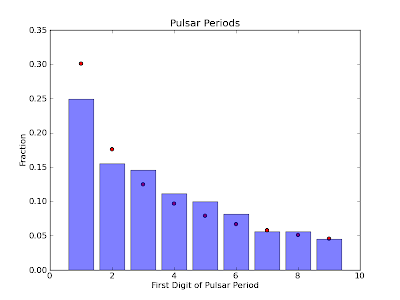

periods. I took 1875 pulsar periods from the ATNF Pulsar Database (found

here). The results

are plotted below. The bars represent the fraction of numbers that start

with a given digit and the red dots are the fractions predicted by

Benford's Law.

But we can quantify this, too. For a first digit on the interval [1,10),

the probability that the first digit is d is given by:

$$ P(d) = \frac{\mbox{log}(d+1)

-\mbox{log}{10}(d)}{\mbox{log}(10) -\mbox{log}{10}(1)} $$

which is just $$ P(d) =\mbox{log}(d+1) -\mbox{log}{10}(d) $$

or $$ P(d) = \mbox{log}\left( 1 + \frac{1}{d} \right) $$ which

is the distribution of Benford's Law. So how well do different data sets

follow Benford's Law? I decided to test it out on a couple easily

available data sets: pulsar periods, U.S. city populations, U.S. county

sizes and masses of plant genomes. Let's start first with pulsar

periods. I took 1875 pulsar periods from the ATNF Pulsar Database (found

here). The results

are plotted below. The bars represent the fraction of numbers that start

with a given digit and the red dots are the fractions predicted by

Benford's Law.

From this plot, we see that the pulsar period data shows the general

trend of Benford's Law, but not exactly. Now let's try U.S. city

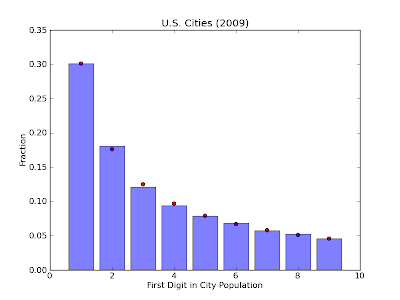

populations. This data was taken from the U.S. census bureau from the

2009 census and contains population data for over 81,000 U.S. cities. We

see from the chart below that there is a near exact correspondence

between the observed first-digit distribution and Benford's Law.

From this plot, we see that the pulsar period data shows the general

trend of Benford's Law, but not exactly. Now let's try U.S. city

populations. This data was taken from the U.S. census bureau from the

2009 census and contains population data for over 81,000 U.S. cities. We

see from the chart below that there is a near exact correspondence

between the observed first-digit distribution and Benford's Law.

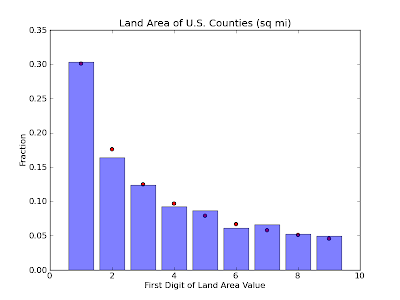

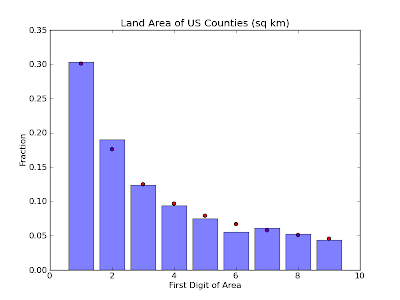

Also from the U.S. census bureau, I got the data for the land area of

over 3000 U.S. counties. These data also conform fairly well to

Benford's Law.

Also from the U.S. census bureau, I got the data for the land area of

over 3000 U.S. counties. These data also conform fairly well to

Benford's Law.

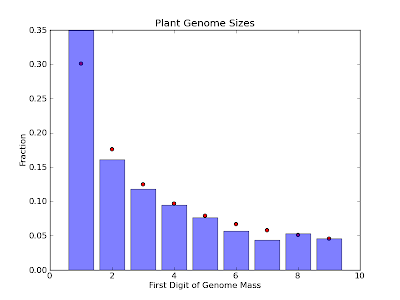

Finally, I found

this neat website

that catalogs the genome masses of over 2000 different species of

plants. I'm not totally sure why they do this, but it provided a ton

of easy-to-access data, so why not?

Finally, I found

this neat website

that catalogs the genome masses of over 2000 different species of

plants. I'm not totally sure why they do this, but it provided a ton

of easy-to-access data, so why not?

Neat, so we see that wide variety of natural data follow Benford's Law

(some more examples

here). But why should

they? Well, as far as I have gathered, there are a few reasons for this.

The first two come from a paper published by Jeff Boyle [2]. Boyle makes

(and proves) two claims about this distribution. First, he claims that

"the log distribution [Benford's Law] is the limiting distribution when

random variables are repeatedly multiplied, divided, or raised to

integer powers." Second, he claims that once such a distribution is

achieved, it "persists under all further multiplications, divisions and

raising to integer powers." Since most data we accumulate (scientific,

financial, gambling,...) is the result of many mathematical operations,

we would expect that they would tend towards the logarithmic

distribution as described by Boyle. Another reason for why natural data

should fit Benford's Law is given by Roger Pinkham (in this

paper).

Pinkham proves that"the only distribution for the first significant

digits which is invariant under scale change of the underlying

distribution" is Benford's Law. This means that if we have some data,

say the lengths of rivers in feet, it will have some distribution in the

first digit. If we require that this distribution remain the same under

unit conversion (to meters, yards, cubits, ... ), the only distribution

that satisfies this distribution would be the uniform logarithmic

distribution of Benford's Law. This "scale-invariant" rationale for this

first digit law is probably the most important when it comes to data

that we actually measure. If we find some distribution for the first

digit, we would like it to be the same no matter what units we have

used. But this should also be really easy to test. The county size data

used above was given in square miles, so let's try some new units.

First, we can try square kilometers.

Neat, so we see that wide variety of natural data follow Benford's Law

(some more examples

here). But why should

they? Well, as far as I have gathered, there are a few reasons for this.

The first two come from a paper published by Jeff Boyle [2]. Boyle makes

(and proves) two claims about this distribution. First, he claims that

"the log distribution [Benford's Law] is the limiting distribution when

random variables are repeatedly multiplied, divided, or raised to

integer powers." Second, he claims that once such a distribution is

achieved, it "persists under all further multiplications, divisions and

raising to integer powers." Since most data we accumulate (scientific,

financial, gambling,...) is the result of many mathematical operations,

we would expect that they would tend towards the logarithmic

distribution as described by Boyle. Another reason for why natural data

should fit Benford's Law is given by Roger Pinkham (in this

paper).

Pinkham proves that"the only distribution for the first significant

digits which is invariant under scale change of the underlying

distribution" is Benford's Law. This means that if we have some data,

say the lengths of rivers in feet, it will have some distribution in the

first digit. If we require that this distribution remain the same under

unit conversion (to meters, yards, cubits, ... ), the only distribution

that satisfies this distribution would be the uniform logarithmic

distribution of Benford's Law. This "scale-invariant" rationale for this

first digit law is probably the most important when it comes to data

that we actually measure. If we find some distribution for the first

digit, we would like it to be the same no matter what units we have

used. But this should also be really easy to test. The county size data

used above was given in square miles, so let's try some new units.

First, we can try square kilometers.

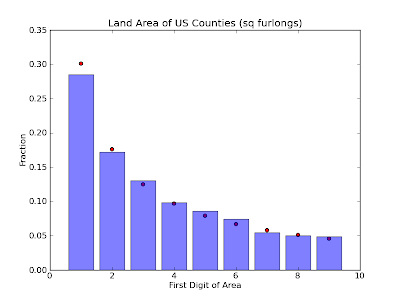

Slightly different than square miles, but still a very good fit. Now how

about square furlongs?

Slightly different than square miles, but still a very good fit. Now how

about square furlongs?

Neat! Seems like the distribution holds true regardless of the units we

have used. So it seems like a wide range of data satisfy Benford's Law.

But is this useful in any way or is it just a statistical curiosity?

Well, it's mainly just a curiosity. But people have found some pretty

neat applications. One field in which it has found use is Forensic

Accounting, which I

can only assume is a totally rad bunch of accountants that dramatically

remove sunglasses as they go over tax returns. Since certain types of

financial data (for example, see

here)

should follow Benford's Law, inconsistencies in financial returns can be

found if the data is faked or manipulated in any way. Moral of the

story: If you're going to cook the books, remember Benford! [1]

Benford's Law, in the great tradition of Stigler's

Law, was

discovered by Simon Newcomb. [2] Paper can be found

here. Unfortunately, this is only a

preview as the full version isn't publicly available without a library

license. The two points that I use from this paper are at least stated

in this preview.

Neat! Seems like the distribution holds true regardless of the units we

have used. So it seems like a wide range of data satisfy Benford's Law.

But is this useful in any way or is it just a statistical curiosity?

Well, it's mainly just a curiosity. But people have found some pretty

neat applications. One field in which it has found use is Forensic

Accounting, which I

can only assume is a totally rad bunch of accountants that dramatically

remove sunglasses as they go over tax returns. Since certain types of

financial data (for example, see

here)

should follow Benford's Law, inconsistencies in financial returns can be

found if the data is faked or manipulated in any way. Moral of the

story: If you're going to cook the books, remember Benford! [1]

Benford's Law, in the great tradition of Stigler's

Law, was

discovered by Simon Newcomb. [2] Paper can be found

here. Unfortunately, this is only a

preview as the full version isn't publicly available without a library

license. The two points that I use from this paper are at least stated

in this preview.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus